Art and human suffering

.

In my March 2022 post Falling Man, I contemplated on the tension between art and human suffering; how art may ignore suffering or even exploit it. Here Auden’s poem “Museé des Beaux Arts” brought out the conflict in sharp contour with sarcasm and biting wit. Recall that the poem was inspired by that famous painting of Bruegel, “The Fall of Icarus.”

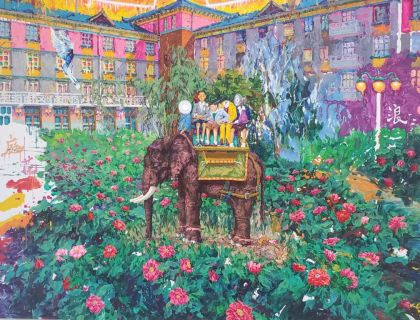

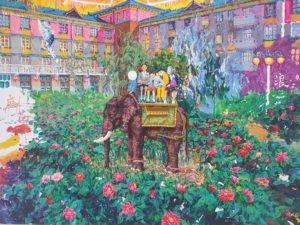

In my recent visit to 798 Art Zone in Beijing I saw the work of Mr. Ming Site in one of the galleries and also met the artist there. These are monumental paintings of apocalyptic scenes that all have one thing in common: most people go on with their business, even while smiling and enchanted, while something terrible — a monster, an eviscerated corpse, a beheaded man — is standing or lying right next to them.

I have to pause here and explain 798 Art Zone, which I visited three times: in 2008, in 2012, and just recently. It is the site of an abandoned military factory built starting in the 1950s by the East German government that called itself “German Democratic Republic” but was a subservient Russian satellite. In 2003 artists flocked to the place and made it their own, creating a vibrant center of creativity in contemporary arts, just the way SOHO started in New York. When I first visited the place in 2008, it had this atmosphere of spontaneity and makeshift. Pop-up galleries and food carts were abound. Artists were busy in their studios, welcoming visitors to watch them doing their work. In 2012 the artist studios still existed, the spontenaity could still be felt, but galleries had become more prominent and fancy. First fashion boutiques had sprung up. Now in my recent visit I hardly recognized the place anymore. It had gone the way of SOHO, with glitzy fashion boutiques, expensive-looking galleries that might have been cloned from today’s Chelsea’s crop of galleries, and fancy restaurants. As in today’s SOHO, the artists have been entirely replaced by commerce. The Wiki article I linked to concludes by saying “what began as a small collection of ephemeral studios and other workspaces has become the third most visited destination in Beijing, after the Forbidden City and the Great Wall.” — Of course, one could make the pedantic comment that the Great Wall is not in Beijing, but we sort of know what they want to say.

Anyway, back to art and suffering. The paintings may be political metaphors hard to decipher for outsiders, so I merely confine my remarks to the literal visceral content: the disparity between the joy of people depicted and utter chaos, dismemberment and agony right next to them. Particularly the scene at the bus station, second painting depicted from below, has apocalyptic character, the result of a violent curse.

Ming Site in front of his happy Christmas painting, 798/Beijing, September 23, 2023

.

So it was a remarkable coincidence that a friend — the same one who had drawn my attention to Auden’s poem — sent me an e-mail the next day from the other hemisphere, from New York, with another poem containing a reflection on the same issue, but here as a defense of joy without guilt: “A Brief for the Defense” by Jack Gilbert.

Guilt is an important element in this conversation, since both the creation of a work of art depicting suffering and its consumption by a viewer may be questioned on moral grounds, much as a form of pornography. Someone who is conscious of these objections and feels they apply to him/her might be struck by guilt. But Gilbert in this poem seems to say that both in art and real life, joy should not be tempered by the knowledge of people in pain and agonies. “We must have/the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless/furnace of this world.” God is the arbiter of guilt in Gilbert’s universe, but we might as well substitute any other shared transcendental concept — and perhaps even Gilbert meant to name God only as a metaphor.

A BRIEF FOR THE DEFENSE

by Jack Gilbert

Sorrow everywhere. Slaughter everywhere. If babies

are not starving someplace, they are starving

somewhere else. With flies in their nostrils.

But we enjoy our lives because that’s what God wants.

Otherwise the mornings before summer dawn would not

be made so fine. The Bengal tiger would not

be fashioned so miraculously well. The poor women

at the fountain are laughing together between

the suffering they have known and the awfulness

in their future, smiling and laughing while somebody

in the village is very sick. There is laughter

every day in the terrible streets of Calcutta,

and the women laugh in the cages of Bombay.

If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction,

we lessen the importance of their deprivation.

We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world. To make injustice the only

measure of our attention is to praise the Devil.

If the locomotive of the Lord runs us down,

we should give thanks that the end had magnitude.

We must admit there will be music despite everything.

We stand at the prow again of a small ship

anchored late at night in the tiny port

looking over to the sleeping island: the waterfront

is three shuttered cafés and one naked light burning.

To hear the faint sound of oars in the silence as a rowboat

comes slowly out and then goes back is truly worth

all the years of sorrow that are to come.

.

.

This entry was posted in Blog and tagged 798 Art Zone, artists, Auden, Beijing, Bruegel, Chelsea, China, Christmas, corpses, elephant, Great Wall, Icarus, Ming Site, paingalleries, SOHO. Bookmark the permalink.

Leave a Reply