Watership Down and Uluru — countable and uncountable

.

Looking back, I cannot recall the moment when the concept of cardinal numbers entered my horizon. It seemed preordained, and could not have emerged gradually, but with a sudden moment of Eureka! And the Arabic system of naming numbers in their sequential order, not by idiosyncratic names as in Borges’ Funes phantasy, seemed part of an unquestionable Platonic world order.

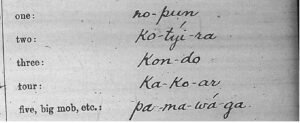

In WATERSHIP DOWN, that wonderful children’s book by Richard Adams, the rabbits are sentients, possessing both a language and their own numbering system. The survival in their adventures — after the clan is deprived of their habitat by human machinations beyond their understanding and is forced to migrate into unknown territory — rely on such basic communication. In that system of numbers, they distinguish one, two, and a number called hrair, meaning both infinite and enemy — which is quite logical since for rabbits the enemy is countless and everywhere. I always considered this a brilliant invention, but this year’s trip to Australia taught me otherwise. The guide on our excursion to Uluru, the great rock in the middle of Australia, told us that most of the 250+ Aboriginal languages will count to a small number, like four, and what comes after is “mob” or “many.” Here is one example, in Gugu Yimiddhirr:

(From State Library of Queensland, Indigenous Number System, Sep 9, 2014. This library is compiling a list of numbers from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages across Queensland and will place these online for use by communities, schools, kindergartens and other groups. The Indigenous Numbers wordlist can be found on the State Library’s Indigenous Languages webpages – they feature over 70 Indigenous languages and dialects).

The rationale for this limitation is seen in the fact that life in this climate is extremely difficult, and all thoughts and activities and the basis of their culture are focused on survival. So much so that the locations of waterholes or the way to find and cook berries that are nontoxic are ingrained in the songs and myths of each tribe. When hunting kangaroos the total number of them – 16 or 29 or 42 – is irrelevant. What counts is the ability to separate and kill two of them, which typically suffices to feed a hunting team and their families.

Not missing in this contemplation on one, two, three and many should be the book by David and Ricardo L. Nirenberg: “Uncountable — A Philosophical History of Number and Humanity from Antiquity to the Present.” In my appreciation of this oeuvre I wrote

“Ricardo and David Nirenberg, father and son scholars of mathematics and history, have teamed up in a breathtaking voyage examining the foundations and limits of knowledge in western thought. Not content with secondary sources, they have translated from the literature in their original languages: Arabic, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Latin, and Spanish. In particular, they target mathematics and the natural sciences, and the way the concepts of sameness and differences affect our understanding of the natural world. But in the process, the authors touch upon many other facets of human endeavor, all named after their Greek roots: poetry, philosophy, psychology, economy. Along this wildly entertaining journey, we meet dozens of erudite thinkers, scientists, and writers such as Anaximander, Al-Fārābī, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Werner Heisenberg, and Rainer Maria Rilke. The book arrives just in time to give us ammunition as attempts are being made to put truth itself into the supercollider. It is a source of inspiration and comfort to learn how the far-flung ideas about numbers, our existence, and the world we live in have been debated in the past.”

.

.

Leave a Reply