A museum for Cajal — no longer a dream

.

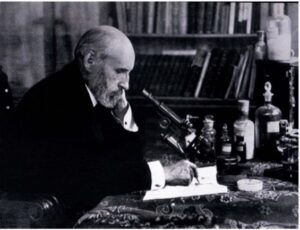

Santiago Ramon Y Cajal was the pioneer of neuroanatomy. The importance of his early contributions to the evolving field of neurophysiology cannot be overstated. Looking at brain slices stained with silver nitrate (following Golgi’s protocol) and using the light microscope, he was the first to map the different types of neurons, their interconnections and distribution in the brain. Many ink drawings he meticulously made showed intricate networks of neurons never seen before.

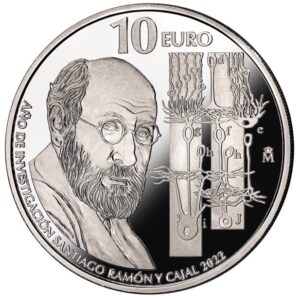

Much revered in Spain, he is one of the nation’s first Nobel laureates with the Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906, the second of seven Nobel laureates in Spain. A ten-Euro coin ensures that his face and discoveries will be known even centuries from now, at worst — if the pessimists are right — from archeological digs. Most recently, during and after my recent visit to Valencia, Cajal became a focus point of my interest. The following explains how this came to be.

I gained a real understanding and appreciation for his gigantic work when I had a chance to see a special exhibition in his honor a few years ago (pre-Covid-19) in Valencia, where he was briefly professor of anatomy at the university before he moved to Barcelona, and where his interest turned to the study of neural connections in the brain.

Unfortunately, Spain where the pursuit of science is not easy for lack of adequate funding, has been unkind to him until most recently. In his own words, “to do research in Spain is to cry.” But it’s more complicated than that, as I learned from an article published a few years ago in the States, since part of the reason has been the unwillingness of Cajal’s estate in the hands of his family and descendants to make his documents available for government-curated public access.

As a commentary published in 2022 by a pamphlet of the Real Instituto Elcano stated,

“For almost 40 years, most of Cajal’s legacy, including 2,000 handwritten manuscripts, 14,000 histological slides and 2,000 scientific drawings have been stored at the Cajal Institute, part of CSIC. Until 1997 they were kept in shameful conditions. With 2022 officially declared the ‘Year of Ramón y Cajal Research’ and Cajal’s voluminous archives registered in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register since 2017, it is a scandal there is still no museum on the great scientist, despite repeated promises. All that is lacking is the political will.”

Importantly, his legacy also includes a large trove of artistic photographs unrelated to science, as well as pieces of fiction writing, memoirs and even several novels.

But how do I know and why do I care about Cajal’s work? It is of course part of college education in biology, which I never received during my Freiburg time as a student of physics. But later, in Munich, I got introduced to it by my friend Wolf Singer, who was receiving training in neurophysiology. Now of course, many years later, and in the times of computer-simulated neural networks, we all carry with us in our minds (an automorphic mapping, so to say) the images that Cajal first discovered more than a century ago. Still, the fate of his legacy in Spain was unknown to me until most recently. And I found out about it in the following way:

As one of the jurors of Prix Rei Jaume I, the prestigious Spanish science prize awarded each year, I visited Valencia earlier this year again, and this time an entire extracurricular day was devoted to Albufera, the large wetland and wildlife area south of the city. We learned about the century-old struggle to wrest the wetlands from years of industrial abuse and start managing it responsibly as a natural resource, a task now in the hands of the Valencia province. We learned about the annus mirabilis 2022, when the number of flamingo couples reached a staggering 10,000, perhaps as a result of the lull in tourism during Covid-19. After an educational introduction we toured the wetlands on the same kinds of boats that once carried Cajal around the lake. The members of the jury – around 50 scientists all in the six different categories of the award – were later asked to sign a declaration petitioning UNESCO to designate the Albufera Natural Park as a World Heritage Site in the “Biosphere Reserve” category.

It was on this occasion where I ran into Maria Pedraza again, who has a Ph.D. in neurophysiology and has made major contributions to the study of the development of the cerebral cortex. A native of Valencia, her association with Cajal is professional, emotional and direct since one of her previous workplaces was the Cajal Institute in Madrid. I had first met her a year ago during the previous Prix Rei Jaume I events. In Maria’s view, Cajal was one of those rare people with creativity and passion for both science and the arts, and in that a model for the unity of humanitarian vision that has slipped away from us since. Here is her own account of her connection with Cajal, in an essay she distributed to her colleagues and friends.

It was just a couple of weeks later through her, after I had returned to New York, that I received the news about Cajal’s final triumph, the kind of news that scientists in Spain and the rest of the world have been waiting for. It was dated June 25, 2024:

“The Council of Ministers has approved this Tuesday the royal decree by which the Museo Cajal is created, as a National Museum with state ownership, under the purview of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, whose objective will be to spread and do justice to the universal values of the legacy of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1906 and ‘universal’ pioneer in neuroscience.

“The royal decree establishes the central headquarters of the Cajal Museum in the city of Madrid and contemplates the possibility of setting up branch offices linked to the museum in other Spanish municipalities “through the subscription of the corresponding legal instruments of collaboration between the different administrations, entities and organizations interested.”

Here is the original text: “El Consejo de Ministros ha aprobado este martes el real decreto por el que se crea el Museo Cajal, como Museo Nacional de titularidad estatal, dependiente del Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades y cuyo objetivo será difundir y hacer justicia al valor universal del legado de Santiago Ramón y Cajal, premio Nobel en Fisiología y Medicina en 1906 y pionero ‘universal’ en la neurociencia.

“El real decreto fija la sede central del Museo Cajal en la ciudad de Madrid y contempla la posibilidad de poner en marcha sedes filiales o vinculadas al museo en otros municipios españoles “mediante la suscripción de los correspondientes instrumentos jurídicos de colaboración entre las distintas administraciones, entidades y organismos interesados”.

So it will not be long, we hope, until we can admire the master’s ingenuity and creativity first-hand.

.

.

This entry was posted in Blog and tagged Albufera, Biopsphere Reserve, Cajal, CSIC, flamingos, Museo Cajal, Prix Rei Jaume I, UNESCO, Valencia. Bookmark the permalink.

National Geographic

National Geographic

Leave a Reply