.

Published on September 3, 2024

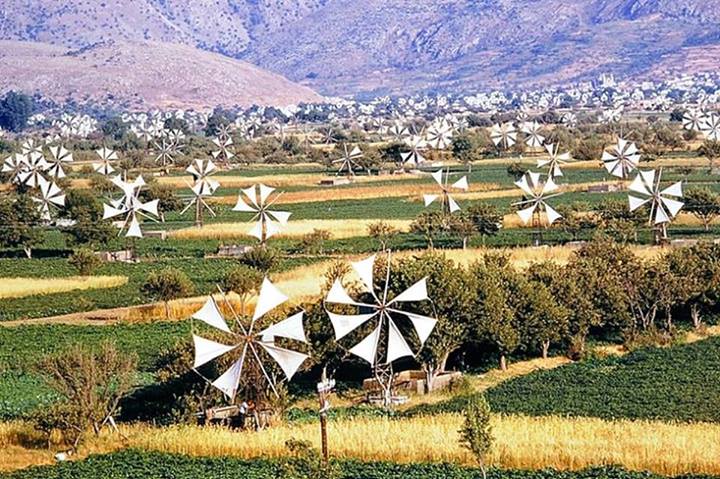

IERAPETRA, OR HIS SISTER’S KEEPER — This (postmodern) novel is about the attempt of a man to overcome grief and guilt through story telling. The narrator (German-born scientist, now in his 70s and residing in the Berkshires) reminisces about the times he spent with his three-year younger sister, who succumbed to cancer in her early fifties. His memory centers around traumatic events during a trip he took with her to Crete during his college time, in the nineteen sixties, which left her with emotional scars and him with a perpetual feeling of insufficiency and guilt. Catalysts of these events were two tourists, a quirky Spanish woman and a self-important German student, whom they met on the trip. The narrator’s attempts to write about the events on Crete and their aftermath in the first person are futile, so he appoints a stand-in, Reiner, to recapitulate in his stead the Crete trip with his sister and the years after until her untimely death, in a conveniently distanced third-person story. Several times the narrator feels compelled to intervene at places where he believes Reiner is taking too many liberties, even to the point of heretically asserting his own agenda, free of concerns for the well-being of his sister. More than once the story touches upon their experience of growing up in post-war Germany in a provincial, puritan town. Between glimpses of its ancient cultures, Crete comes to life in its spectacular atmospheric light, its own brand of Greek island music and the vitality of its people. We hear of European echoes of the Vietnam protests and see hippies flood pristine beaches. Accounts of Reiner’s journey to Crete and his later meetings with his sister and the Spanish woman are illuminated by his reflections and diary entries. The relationship between the two siblings is marked by their claustrophobic upbringing, which they have been seeking to overcome, and later by the liberation of creative impulses after their father’s death.

.

.

A year ago, when it was still unpublished, I found a writeup of IERAPETRA on the Spanish website CNB DIVULGA, an online publication of Madrid-based Centro Nacional de Biotecnologia, posted on October 14, 2022. The piece is called “wantstobeawriter”, which I used as a moniker on my twitter profile. Ironically, it was in October 2022 when I decided to leave twitter as I could not stand to be part of Elon Musk’s madhouse. Here is the Google translation:

WANTS TO BE A WRITER

by Carlos Pedrós-Alió

Dieter remembers that trip to Crete with his little sister painfully well. The one who died of cancer shortly after, leaving a void impossible to fill. The things that happened on that trip, the encounters with a unique couple, the Mediterranean light and the Greek ruins are mixed with his sense of guilt, of not having been by her side enough, perhaps even of having betrayed her. This is, approximately, the synopsis of a novel titled “Ierapetra, or his sister’s keeper.” It doesn’t really attract much attention, right? We could imagine the outcome and remember novels with similar plots. We might wonder if it is worth reading or not. But we will not know this. Because this novel has not been published. And the most unique thing is that the author is one of the winners of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Joachim Frank developed a technique to improve the resolution of electron microscope images, so that we can now “see” molecules. Units so small that before their invention they were only seen as a blur. The consequences of this advance are being spectacular. For example, researchers at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne were able to observe the famous “spike” protein of the omicron variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and identify the mutations that allowed this variant to become resistant to some vaccines. In fact, the CNB has one of the best cryo-electron microscopes in Europe, which takes advantage of the discoveries of Frank and his colleagues with whom he shared the Nobel Prize. But what interests me is that Frank puts “wantstobeawriter” in his mini-biography on Twitter. Frank always explains his frustration because he has already written four novels, but cannot find a publisher to publish them. He has only been able to publish a few poems and short stories in various magazines. He also has a website in which he says: “I started this site because nowadays one needs a presence to be present and physical presence is no longer enough to be seen in this nebulous virtual space.” That website is where I got the synopsis of Ierapetra.

Map of Crete, with the travels of the protagonist marked:

REVIEWS/Comments

In “Ierapetra, or His Sister’s Keeper”, Joachim Frank’s splendid new novel, we find ourselves in the company of Reiner and his sister Monika. Reiner has two passions, science and writing. Monika has family and quilting. We accompany them on holiday to the Island of Crete. We are immediately immersed in an archetype, innocents abroad in a challengingly unfamiliar culture, in this case two youths from the stern clime of northern Germany transported to the sunny sensuality of the Mediterranean. The powerful narrative that pulls the reader relentlessly through the novel from beginning to end is familiar. What effect will culture shock have on our siblings while they are in Greece, and will it persist when they return home? Will their old commitments survive?

If on the sequestered island sun-burnished flesh is seductive, then there may be seductions. If a certain moral laxity colors the ambience of the island (a condition against which strictest barriers have been raised back home in Germany), then there may be tests of moral character. And so there are, both. Reiner, a straight arrow, may, under the tutelage of the delightfully bawdy Rosa, a sort of benign Carmen, learn to curve. Monika, an ingénue, may discover a genuine femininity in the arms of the bumptious but seductive Bernhard, a wannabe architect mucking about in Greece. Each in a characteristically different way will have to deal with deviance from the traditional values. Their trials are tense and moving.

So, character and plot give the novel a powerful base, but there are other uniquely valuable treasures. One is richly layered symbolism. The scene is Ierapetra, which means sacred stone. Stones are strewn over the beaches of Ierapetra. They assume a darkly numinous quality in the mind of Reiner, glowing like lanterns, filling him with dread. Reiner remembers himself and his sister Monika as children pretending that the quartz stones they found in their yard in Germany were gold. Later at Monika’s burial site Reiner reflects on the obdurate refusal of headstones to express the richness of human complexity. Nor do these instances exhaust the meanings Frank has attached to stones.

One can enter the novel by way of its title, “Ierapetra, or His Sister’s Keeper” and its dedication “In Memoriam Renate 1944 – 1998.” Was Reiner a dedicated keeper of Monika? Was Joachim Frank of Renate? This double signification of brother and sister brings us to Frank’s ingenious layering of presumed reality and fictive invention. Early in the novel the author decides that telling the story in the first person will not work. He must distance himself from memories likely to prove unmanageable. Thus is born his avatar Reiner and the invented sister Monika. The artistic result is a kind of elegant scrim that most often foregrounds Reiner and Monica, but sometimes becomes almost transparent and reveals Joachim and Renate behind. The effect, powerful but difficult to describe, is an alternation of tones—elegiac, remorseful, foreboding, comical, contemplative—as the dominance of foreground or background at any moment engenders.

Is there a central theme that binds together the various riches of the novel? Early in the novel Frank, not yet creator of Reiner, is reminded of a flea circus he once watched in Copenhagen. What fascinates him is the fitful starts and stops of the fleas as they execute their acrobatics, “the counteracting forces that caused them to restart capriciously and at random. Until then, I think I had conceived the world as a giant Cartesian machine, where random lapses were inconceivable. At that moment, I realized these suspensions of the rule of determinism were in fact commonplace.” This is very close to the center of the novel. Are our lives just a random one thing after another? Or does what happens to us inevitably cause what we are? Or Heraclitus’ “character is destiny?” Or . . . what? We are confronted with a great mystery about life. And as long as it remains a mystery there will be a place for magical fictions like Ierapetra.

– Eugene Garber, author of Maison Cristina and The Eroica Trilogy, in Offcourse #98, September 2024

This is a very interesting and striking novel. The language both in terms of the descriptive passages and the dialogue is evocative and complex. The dynamics between Germany and Greece, between Crete and Manhattan in that wonderful closing and bracing passage, between siblings, and between the contemplative/narrative viewpoint and an individual who might forever be beyond meaning or understanding are well rendered. It is a compelling and at times summer story, and the reader is always worked.

– Nicholas Birns, author of Theory After Theory and Contemporary Australian Literature

Just a quick note to tell you that I enjoyed your book thoroughly. The German allusions and story resonate with me (I did my PhD and first post-doc in Regensburg). I like very much the “Leitz episode” (I also still have one with papers of back then). Ierapetra, and its so unusal beach pebbles, is special to me since I spent a honeymoon there with my second wife more than 40 years ago. But you were there way before…

The way you describe the arrival, by the road, at Vai is exactly how I remembered that first view of the palm trees. And the way you describe a scientific meeting, like the one at Sitges, reflects with undertones the experience that all scientists live. The book illustrates beautifully that we are all “hidden in many layers.

– Eric Westhof , Strassbourg, e-mail December 22, 2024

Thanks the book Ierapetra did arrive in November thanks and I read it almost in one sitting and I will have to read it again.

– Bob Cordia, Sydney, e-mail December 21, 2024

Thank you for gifting a great piece of literary work to humanity, your beautiful book “IERAPETRA, OR HIS SISTER’S KEEPER” Heartfelt, Genuine and Genius!

– Bhanu Jena, Detroit, e-mail October 17, 2024

.